No one had any idea of what would happen in the next few minutes …

You haven’t seen this? the Shanghai storekeeper asks. You really should watch it.

The video CD costs twelve RMB, or a dollar and a half U.S. Hastily assembled for mass consumption in under a week, the packaging shames that of pirated movies and music albums. Surprise Attack on America: the Chinese characters for America are shot through with seismic cracks. Billowing bits of the World Trade Center rain like meteorite sparks. Rescue workers are on the move — doppelgangers for the brawny action heroes who populate nearby covers.

To the Chinese, one RMB is roughly equal to the value one U.S. dollar holds with us. A meal at the local KFC is fifteen RMB. A taxi ride is a prohibitive twenty RMB or more. Still, the crowds congregate, wrinkled bits of money are passed, and flimsy plastic bags stretch tight as skin about the video CDs.

You should watch this, she repeats. It’s really amazing. She gives me a thumbs-up. In China, the women are the hawkers; the men hang back, mute and lazy.

Surprise Attack on America plays on the store television. Generic New Yorkers loiter on generic streets; later I learn that this footage is from the movie Wall Street. After three weeks in China, American sunshine is an improbable sight. Cut to a wide shot of the World Trade Center from the Hudson. A clumsy computer-generated targeting sight has been superimposed on the towers, dramatizing the tragedy to come.

Jesus Christ, my friend Jack half-laughs. As I smooth out a few bills, he snorts: I can’t believe you’re buying that …

The crowds stare at the television, revisiting looped footage. The second jet plows into the tower. We see the conflagration again, this time from a street-level angle. Yet another street angle. It seems like a cruel joke: the jet is reconstituted, only to be destroyed, only to be reconstituted again. The people of Shanghai witness these acts of reincarnation, their eyes open and steady.

***

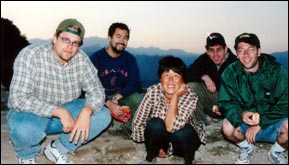

At Simatai, the Great Wall lies dormant, unspoiled by renovation, canned music, tour groups. It is a good three-hour drive north from central Beijing, but our driver Mr. Fu covered the distance in under two and a half. Todd and I bounced about on the minivan’s spongy back seat, blinked at the dust and gas fumes. Todd was telling us about his Chronicle article that exposed a Silicon Valley executive as a lying fraud; the man had subsequently been booted from the company. At one point we momentarily drifted into the path of a flatbed truck, and Carrie let loose with a thrilling eek.

Night had already swamped us when we arrived at the entrance to the Wall. We could hear radios and barking dogs from a commune a few miles away. Mr. Fu, all smiles and diplomacy, negotiated with the guards at the gate.

The Wall closes at four in the afternoon, one of them said. He seemed uninterested in even the sound of his voice.

All right, Mr. Fu replied agreeably. We’ll go around to the other side, then. I hear there’s a way in near the 16th tower…

In the darkness, the two guards exchanged a look breathtaking in its economy. The silent communication was clear: If they leave, we get nothing out of this —

All right, the second guard gruffly conceded. Thirty RMB each person.

***

Lhasa’s circular Barkhor District is one of the last vestiges of Tibet from pre-occupation days. We negotiate the cobbled alley, adopting the clockwise route of the pilgrims who have traveled hundreds of miles to this place. Covered in the glare of unadulterated sun, I feel as if we are in a most comfortable oven. Tibetans murmuring to themselves continually shove past, knocking me off course by degrees. Prayer wheels with round metal stems whirl in their hands. Something in the movement reminds me of youth, and the hypnotic motions of a pinwheel. On the subject of Tibetan prayer technology, Jack makes a crack about “prayer pianos.” We forgive him; the altitude sickness has impaired his sense of humor.

Smack in the center of the Barkhor is the Jokhang Temple, wreathed in a seething mist of incense. Pilgrims prostrate themselves and offer prayers before the chapped wooden front door, which rises two stories high. Carrie stops one of the red-robed monks, and asks directions in fluent Chinese — not for nothing did she live in Beijing for a year.

The monk scowls at her. I am not Chinese, he says in English. I am Tibetan.

Moments later another monk halts us at the temple entrance. The ticket is twenty-five RMB, he says. Neither happy nor unhappy, he is just there.

Really? Carrie’s husband Erik says. Our guide book —

— says it’s free, the monk finishes. But it’s not right.

Carrie stands there, both winsome and helpless. I very much envy her at that moment. When she is here, far from San Francisco and the prosaic reality of technology beat writer for the Chronicle, she seems attentive, bubbly with curiosity, young, enlightened. I can only see a man asking for twenty-five RMB.

The monk, perhaps softened by our silence, then asks: Where are you from?

America, we answer.

Oh. He scratches his head, as if embarrassed. We are very sorry for you. Okay, you can go in free.

We smile nervously as we thank him. I wonder how many Americans have passed through this gate since September 11, and how many of them have gotten through without a fee.

***

The night we returned from the Wall, Carrie and Erik invited us to meet their old colleagues from Beijing Scene, the city’s first English-language weekly, now extinct. Naturally, we conducted our wake over a Peking duck banquet — one friendly decadence the city has never forsaken.

The restaurant was right off the Third Ring Road, throwing purple and yellow neon from an intricate sign two stories high. Inside it was ramshackle and voluptuous with aqua decor and dusty thick curtains. Air conditioners clacked, plates and glasses clinked, and the tablecloth drooped over my knees. I was seated between two pleasant Chinese men, and I exchanged inoffensive words with them — they seemed like twins in facial features, eyeglasses, even their round bodies.

On this night I was ruminating. Since my last visit, Beijing had changed like every Chinese city does — faded, gritty alleys replaced with four-lane highways, alien lime floodlights irradiating construction sites at night, whole geographies of shopping centers and gated apartment complexes conjured from nowhere. All my old friends had left or fallen out of touch, and once again, I was merely a tourist, a disoriented stranger among strangers.

Carrie and Erik’s friends looked my way every so often, but I refused to complete the circuit of acknowledgment and initiate conversation. Jack and Todd were engaged with their neighbors, everyone was baldly commenting on Erik’s new-found paunch, and every few minutes Carrie was shouting greetings to another friend, laughing about the demise of Beijing Scene. The day before, we had wandered over to the office site, and discovered a reef of earth-toned rubble.

Carrie introduced me to Dave — a local musician, a fluent speaker of Chinese, friend of remarkable friends, thin and cool and laid back. She mentioned I was into filmmaking. Dave looked at me as if to say Oh really? and I didn’t elaborate beyond an embarrassed smile. He mentioned some local film connections he had, but the subject seemed remote to me.

Dave knew of a dive in Sanlitun, the expat bar district, that sold rum and cokes for ten RMB. A handful of us took the twenty-minute stroll to the bar, the boulevards long and endless. It was one of those pleasant clear summer evenings in which the sodium streetlights burn like lonely planets. Chinese drivers still know not to hurry, and the long-winded whish of passing cars was punctuated by the occasional bicycle bell. Like most cities, Beijing is different at night; unlike most cities, it gains composure after dark.

As we arrived at the bar, Dave was on his cell phone, cigarette nervously jutting from his mouth. A plane’s crashed into the World Trade Center, he said.

One of his Chinese friends was on his own phone. Six people dead, he interjected.

Yeah, right, was my first thought. Just six? Another crazy rumor.

Dave had CNN International at his apartment, and invited us to accompany him. He lived in one of the diplomatic compounds — I never learned which one, or why he lived there, as he had no discernible job. Four of us squeezed into his black mini-SUV, the rest trailing behind in other people’s cars. Soon we were rolling down barren streets. Despite the paved concrete, the manicured bushes, I felt as I did the first time I had ventured through Beijing at night: One can easily get lost in this jungle.

***

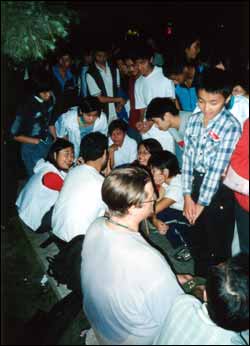

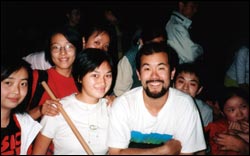

In Chengdu, central-west China, English Corner is held every Wednesday and Friday night along Renmin South Road, near the Jin River Bridge. People of all ages and occupations gather to practice their English. More precisely, they seek out native English speakers, swarming them as if they are the latest pop idols. Two types populate English Corner: the talkers and the listeners. The talkers will pound away with questions, while the listeners strain forward, eyes furrowed, mouths moving soundlessly as they try to retain the memory of the English speaker’s lips, their particular accents. The Corner is held in near-complete darkness, granting participants anonymity and courage.

On this night, the air is still foggy with the residue of today’s rain. Gingerly, I am approached — surely this Asian man can’t be a native speaker — and when it is discovered that I am American born and bred, the disciples gather. Erik, charming paunch and all, is a hit from the get-go. Most of the talk centers on innocuous subjects. Do you play a lot of tennis in America? How hard is it to find a job there? What do you think of that Crouching Tiger movie? (I told them I was ambivalent, but they all loved it.)

Finally, the question comes: Have you heard about the plane crash? Many people have asked me this question in the week since September 11. Some merely mimic the crumbling of the towers: a raised hand, flat as a board, then the wrist goes limp and the hand collapses. Others shake their heads with an ambiguous grin. Still others are more specific: What’s the news? Any military news today?

I ask them for their opinion. They speak words of sympathy, they say it is a terrible thing, but they do not seem especially troubled. Later it is reported that many Chinese took a perverse joy in the tragedy; America, the world’s bully, had finally been punched in the nose. No one in this crowd gives me this impression, but all seem to treat the incident as merely another tragedy in a tragic universe.

There’s an apocryphal story in which a foreigner cracks a tooth on a random pebble which has found its way into his rice bowl, and his Chinese companions laugh at his groan of pain, the bits of enamel that plop into the rice. A nervous laugh is a conditioned response to misfortune. Perhaps history has inoculated the Chinese against dramatic responses to the pain of one, or even a few thousand.

Carrie tells me she has been talking to a young man who is very eager to visit Tibet. He was pissing me off, she says. He was boasting about how the Chinese have helped develop Tibet, and how the land there is now rich and fertile.

***

Drigung Til Monastery is ninety kilometers and several centuries east of Lhasa. Situated near the top of a mountain range about seventeen thousand feet high, its crimson walls blend with the parched landscape. The monastery itself is a collection of stone-dark rooms and rooftop rubble waiting to be rebuilt. Soon all thoughts fade away from the actual structure and are whittled down to the spartan fields of grass, the bundles of sticks and hay dotting the landscape, yaks wandering down the path in pairs, their earrings denoting territory and ownership. Yak chips are flattened into discs and left to dry in the sun; in the winter, they will be used as fuel. A thousand feet below, a river carves up the valley floor, the waters clear and blue like diamonds.

We arrive with backpacks burdened with ramen and horrendously bitter cookies, and the monks gather around us. They are quiet but eager, their heads shaved military-style, their robes clean and voluminous. One of them listens to my minidisc player (Radiohead, “Pyramid Song”), and asks if he can keep it. A seemingly outrageous request, but even in China, America is assumed to have streets of gold — surely I have two or three more minidisc players at home? He shrugs off my polite refusal, but the two village children are unswayed; I possess wealth, I must have pocketfuls of it. For the next two hours, they beg us for money with droning persistence: Please, please, please. Carrie and Erik placate them with Jolly Ranchers before the monks swat them away.

Later we discuss September 11th with one of the younger monks. His eyes are sunken and he has a loping swagger, a sweet grin: inner city kid in another life. We can barely understand his strangled Chinese, but the meaning is clear enough: something about those damned Afghans, something about that damned bin Laden. He flips Osama the bird, and we all laugh at the unexpectedness of the gesture. Occasional fights break out between the monks and villagers below; our monk is pleased to show us the bruises from a fracas a few nights before.

Pilgrims en route to Lhasa for the first time are among the monastery guests, and browse our guide books. They cannot read English, but they pore over the pictures like code. They are even more engrossed in the photos of China: the jagged urbanscapes, the rice fields drowned in plentiful water. Strange how a place a few hundred miles away becomes as unknown and mystical as a dream.

Atop Drigung Til Mountain is a sky burial ground. Almost every day, bodies swathed in white like mummies are solemnly carried into the courtyard. The monks assemble, perform last rites, and transport the body up to the burial ground. There it will be chopped to pieces and left for the falcons and vultures to eat. In return for this service, the deceased’s relatives present bags of rice, money, and other necessities to the monks.

A boisterous group of Swiss tourists has also arrived, and we catch them between beer breaks to ask: We’re going to try attending a sky burial, do you want to join us? They shake their heads with slight exasperation: No, foreigners aren’t allowed to see them. One can practically hear the thoughts in their heads: Silly Americans, they think they can do anything.

Early in the evening, the first body of the day arrives. It is a three year-old boy, and the bundle is small and stubby, like an outsize cocoon. The ceremony will be in the morning, and we ask our monk if we can attend. Sure, no problem, he says lazily.

I am seized with the desire to see the sky burial ground before the actual ceremony. Jack accompanies me partway, but the altitude sickness is taking its toll, and he must retreat. Alone, I tread the rough dirt paths, winding around single-room dwellings that serve as the monks’ quarters. Moss and lichens frost many of the stone doors, and many of the houses seem completely deserted. Above, the sky is a lucid blue, while a thousand feet below, the river gushes on and on. Pain singing in the space between my ears, I press forward, legs like weights at this altitude. Seeing the burial ground is now an urgent imperative, as if I am making the lonesome trek to my own final resting place.

***

An old man has been sitting patiently at the English Corner, observing me talk to the trio of chipper high school girls who have monopolized the conversation. He is dressed in a dusk-gray, unwrinkled jacket, as many older people are, and wears thick glasses. I feel protective of him, as if he is an uncle who has misplaced his car keys.

Finally he speaks: Excuse me. May I ask you a question?

The simplicity and politeness of the words give me a shiver. Was there a time when all people everywhere acted like this? Maybe we would like to think so. It is our collective dream that people are kind and courteous, and we are driven to believe in such fantasies.

Of course, I answer in the most encouraging tone I can muster.

He pauses, gathering up the words. Finally he says it: What do you think about the incident on September 11?

The high school girls burst out in almost perfect chorus, reverting to Chinese: We already talked about that!

No, no, it’s okay, I say, but the damage is done. The man is giving short spastic nods of the head, shrinking in apology. Undeterred, I press on: Well, it’s a very … What is the word? Is there an easy, understandable way to say it?

A very sad thing, I finish.

***

There are no words. There are no words.

Around 10:05 p.m. Beijing time, the CNN reporter could only mumble those lines, over and over, as the South Tower collapsed. Oh my God, Dave muttered. Twenty-five thousand people in there …

There were a dozen of us, a motley assembly of Americans and Chinese and all those in-between, slumped on the sofa, cross-legged and upright on the floor, standing, pacing, unable to articulate beyond indrawn breaths, tiny shakes of the head no. As the hours passed, Dave’s Chinese friends dropped in. Some gravely took a seat on the floor, saying little or nothing; others stared at the television for a few moments, hacked out a laugh — the conditioned broken-tooth response — and then stared some more, grins paralyzed on their faces. Dave’s roommate Christiaan and his chain-smoking Chinese girlfriend showed up. He had an unidentifiable European accent, and his eyes lit up strangely when Dave gave him the news. Really? he said. Really? Later he passed around business cards; he was a DJ and Asian music expert, and was scheduled to have a show in New York later that month. His girlfriend curled up on the floor in front of the television; I noticed her toenails were painted black.

A hysterical eyewitness was being interviewed — she saw a mother and her baby getting trampled in the confusion. Carrie let out a sob and leaned hard into Erik, her eyes watering over. Dave was flitting between the living room and bedroom, calling local expat friends and overseas relatives. Jack was trying to send email over Dave’s computer, but the connection was slow and treacherous. Todd was calmly considering flight plans — obviously he wasn’t going home any time soon. Myself, I paced aimlessly, like an animal trapped in an invisible cage. Leaving wouldn’t help; sleeping was out of the question; the television was a mass of conflicting reports; thinking was exhausting but unavoidable.

But eventually people rose with painful breaths, took their leave. The rest of us fell into the same glassy-eyed expressions. CNN was failing to impart additional wisdom. Jack, Carrie, Erik and I looked at each other, and just like that, we knew we had to leave. Dave gave me a heartfelt shake of the hand. We didn’t get to talk, but thanks for coming over, he said. I only nodded. I doubted I would ever see him again.

***

The Fairy of Simatai, we called her. We had reached the eighth tower of the Great Wall after an hour’s climb, expecting to be utterly alone, but here she came, down the rugged walkway connecting us to the ninth tower. She lived there with her husband, inside a hut with metal sidings and a canvas roof. As she approached, we couldn’t even see her. We could only hear her voice floating out to us:

Hello! Where are you from?

After a moment’s pause to gather ourselves — No, this is not a ghost — we answer: America. Where are you from?

Simatai! she yelled, and we laughed at her chipper tone. Bustling and happy, she hunted up twigs and dry grass for a campfire — No! she shouted in English when we offered to help — and sold us beer and orange-honey Jianlibao soda for five RMB each. During the day, she sold food, beverages, and postcards to the tour groups who came here. At night, she and her husband slept in their metal shack. Strange to even think of the idea now: I live on the Great Wall.

A few weeks before, five U.S. soldiers had camped atop the eighth tower, downing over a hundred beers and raising a ruckus. The Simatai woman’s husband recalled the crumpled cans everywhere, the loud shouts throughout the night, but seemed pleased at the memory. Her husband stoked the fire with some strategic burned tissues and tsk-tsked at our scarce rations (only five hot dogs total), but enjoyed watching us burn our marshmallows to goo.

Carrie, Erik, Jack and Todd laid out luxuriously in sleeping bags. I had no bag of my own and relocated inside the tower itself, draping a spare sweatshirt and long-sleeve denim shirt over my middle and legs. The tower floor was clean but dusty, and soon I was caked in it. Open-air doors and windows faced in all directions.

I could only sleep in brief fitful spurts. Several times during the night, I ventured out onto the Wall. My flashlight illuminated faint discs of ground, and I had to treat every step like an command decision. Above me, the others snored, dead to the world. I took a few photos of the tower where we slept, the broken cobblestone of the wall itself: stones slapped onto darkness, a ramp that led off into nothing. We could very well have been on an ancient spaceship, lost among the very bright stars. Ultimately, I sat and stared at the wide-open spaces, my stomach tingling at their vastness even though I couldn’t see them.

Just after five, the sun rose, and the others awoke. Like automatons they took care of the morning feeding first: sweet bean cakes, oranges, Chips Ahoy. Soon it was light enough to see the valley below, the endless serpentine chain of the Wall itself disappearing into the mountains behind and in front of us.

Holy shit, Jack said at the sight. Holy shit. It was the morning of September 11.

***

The burial ground is without ostentation, without majesty, without arrogance. A ring of poles forms a crude circular perimeter around the central burial ground. Running up and down the poles and connecting them are strands of prayer flags, vast multicolored patchworks. Red for fire, yellow for earth, green for water, blue for sky, white for heaven. The burial ground itself is a simple grassy plain. In its center is a slightly indented pit built from stones, and resting on the stones are charred whitish objects which may be bones. Set back from the central site is a mound of yak skulls, possibly the result of special sacrifices. Further away, live yaks mill about, unaffected by time or passing strangers.

I stand beyond the perimeter of the burial ground and free myself from extraneous thoughts. The sun sets and the air begins to bite, but I can tolerate it. I watch the grass wave in the wind, smell the burned odors of early autumn. Hundreds of years this site has been here, and in that time thousands have been carried up the mountain. The bodies remain wrapped in white as they are chopped up into limbs and pieces by the monks, and then deposited in the open space of the pit. If they could still see, they would observe empty, unencumbered sky, and then flurries of wings as the falcons and vultures gather above. I want to say something, make some sort of invocation, but I am afraid that the words would leave my mouth as loud as thunder. I satisfy myself with simply gazing at this quiet, unmoving place as it grows crimson with twilight.

***

In Shanghai, Jack and I meet with Shanno (yes, correct spelling), a student from my English teaching days in Beijing. She now works for an investment bank, but very little about her has changed. She still has a statuesque bearing, a sensible manner, a funny way of pursing her lips when she is puzzled or disagrees with something, an occasional lisp when she pronounces the h sound. Frankly, I have always had a bit of a crush on her.

We are situated in a posh hotel restaurant, and in the corner, a trio of women pluck away on traditional Chinese instruments. At one point they launch into a bouncy rendition of “Turkey in the Straw.” I look over at them, but they don’t seem to notice us.

The plates here are shiny enough to reflect our faces, and the room is heavily padded, our voices deadened the instant they leave our mouths. Jack states that he has no intention of returning to China anytime soon — sure he’s had a great time, but he’s had enough of the urban congestion, the culture shock, the overaggressive, well, capitalist tendencies. I needle him a bit about the altitude sickness in Tibet — he ended up buying an oxygen canister for twenty-seven RMB. I conclude with a whiff of braggadocio that I always enjoy returning here, enjoy the fact that traveling in China is not a luxurious proposition but a challenging one.

Really? Shanno says. But I don’t think you like it here.

What? I say.

I remember the last time I saw you. You told me you were very spoiled. I wholeheartedly

agree. She pronounces wholeheartedly like whole-hottedly.

I’m a bit annoyed with her. I don’t remember saying that, for one thing. Perhaps I am spoiled, like most Americans are spoiled. What can one do about it? It is a fact, not a tendency. But I have holed up in drafty Tibetan monasteries, I have hiked over mountains with only a bottle or two of water for nourishment. Surely this worldly traveler can be cut some slack?

Later in the conversation, as an addendum to another smart-alecky remark, I add, Because after all, I’m spoiled.

Shanno stares at me. I have upset you, she says.

No, no, no, I backtrack, but uneasy silence descends. I gnaw at my overpriced food without passion. I will always be the American. Americans can’t understand or appreciate different ways. That is that. I cannot whine.

The trio is playing a Teresa Teng song, one of the old-style aching ballads that still echo forth from Chinatown karaoke bars from time to time.

A lovely flower does not open often

A lovely view does not exist everywhere

Worries furrow a laughing brow

Missing you brings tears to my eyes

After you leave this night

When will you come back again?

After drinking this cup

have a little something to eat,

How many chances to get drunk are there in one life?

***

President Bush is finally addressing the nation. It is the morning of September 13, around eight-thirty Beijing time, a few hours before I leave for Chengdu, and subsequently Tibet. Outside, a local elementary school is going through its morning routines. Hundreds of kids orderly arranged in the courtyard, dancing jumping jacks as the principal screams over a megaphone: One two three! The children shout out Four! and the cycle repeats.

I don’t remember much of anything from Bush’s speech, only that he spoke in short sentences. Our country is strong. The American people are strong. It was as if he was conducting a language class, and the students who were supposed to translate his simple phrases had fallen asleep. Outside, the principal is bellowing something to the kids, a long and involved speech about service to the motherland and good moral conduct, no doubt. The kids listen dutifully, in silence.

***

On the way down from the Drigung Til burial ground, two local Tibetans approach me. They are both brawny men with whiplike mustaches and beards, wrapped in flowing blue cloaks. Tucked snug in their belts are curved daggers.

My mouth goes dry as one growls something in Tibetan. I have no idea what he is saying, but there is aggression in his stare. I shrug, say sorry in English and Chinese, but the words have absolutely no impact on him. He asks me the question again. I back away, glancing around desperately for a side path, anything that will take me down. The man reaches towards his belt, and I think, This is it. But instead of a weapon he produces a ten RMB note. He holds it before me, and asks another question.

What is the meaning? Perhaps he is offering some service, and in return I am to pay him with Chinese money? Or perhaps he has no use for such money and is simply offering it to me? Or is he threatening me: Give us more of this or we’ll take it from you. His craggy tan face could mean any number of things: gruff helpfulness, steely generosity, criminal intentions. I simply don’t know. Any guesses I have will simply be shaped by my own panic. And I know now — as if I never did before — that the world is dangerous.

I say sorry a few more times, and then beat it down a less-trampled side path. One hundred feet and several bramble cuts later, I am back on the main path. The two men remain where they have been, two puzzled figures in the landscape.

***

Nothing is as unavoidable as U.S. money. Chinese RMB is always looked at in context of the American dollar. One U.S. dollar is 8.279 RMB. Ten U.S. dollars is equal to eight half-decent meals. Six U.S. dollars will pay airport taxes.

Our first night in Beijing, Jack and I received a ride from a pedicab driver to our hostel. Three miles, twenty minutes. I’ll take you for twenty, the driver said. We rattled along busy thoroughfares, buses spitting horn blasts and exhaust at us. The driver asked me who I was; Chinese-American, second generation, I replied.

Your Chinese is not very good, he said with a grin. I get that a lot. Many grins, many similar remarks. You don’t use chopsticks right. You don’t look American. You sure you’re not Japanese?

He asked me about what province my parents are from, my job, how much I make in a month. The Chinese are always curious about salaries, always comparing. We arrived at the hostel, and I handed him a U.S. five-dollar bill in appreciation.

No, he shooed off the bill with an unfriendly wave of the hand. Twenty dollars, American money. U.S. dollars.

This is China, I reminded him. You say twenty, that means twenty RMB.

No, twenty U.S. That’s the riding fee, he insisted.

We got into an argument. Twenty U.S. dollars is the cost of a room for the night. Jack plucked at my sleeve and asked, Is something wrong? Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the hostel security guard standing at the door, looking our way. Much later, I realized I should have yelled for him to come over, told him that this pedicab driver was attempting to steal money. But at that particular instant, exhausted, disgusted, I simply handed over the twenty-dollar bill and said: You guys are just shameless.

No, we’re not the ones who are shameless — he blusters, but Jack and I are inside before I hear him finish. This sort of thing happens all the time. Buying clothes, buying fruit, paying money for anything. Haggling, overcharging, stubbornness. The driver didn’t care about where I’m from, where my parents were born, what my salary is, not at all. And the result is I can never trust a pedicab driver again.

***

We exchanged addresses with the Fairy of Simatai, and paid her the ninety RMB we owed her for our drink and food tab. Tuckered out from a morning of clambering around the wall in the full heat of the sun, Jack plopped down next to her, his mouth hanging open as he caught his breath. She laughed at his exhaustion; a coffee table book had materialized in her hands. Uh oh, here it comes, I thought.

Sure enough: Would you like this nice book? Only eighty RMB. Lots of great pictures of the Wall.

Three years before, I had visited Simatai, and was tailed by a mobile vendor with a cooler strapped around her shoulder. She too had a book, and she followed me from Tower Seven all the way out to Tower Thirteen. It was simultaneously amusing and exasperating to have this dogged, persistent woman tagging along, singing songs and continually peppering me with questions: Another bottle of water? I have some ice cream here, do you want some? Promise me you’ll buy this book, okay? Finally I spent ten minutes haggling a price and bought the book, but as a result I was late descending from the Wall, and missed my bus ride back to Beijing.

Jack, however is firm: No thanks, he smiles. No thanks. He has the advantage of not knowing Chinese — no common language, end of negotiations. But the Fairy of Simatai doesn’t give him a hard time. She just beams at all of us. She has had the excitement of overnight visitors. We have all slept on the Wall, under the stars.

***

The Americans are really something, the taxi driver tells me. We are riding through Beijing, and have already been through the preliminaries: Where are you from? Really? You don’t look American …

Oh yes? I said.

Yep, he says emphatically. The news this morning says that the U.S. Army is getting ready to move into Afghanistan. You gotta like that, when a country is strong enough to react that directly. They’re ready to fly there, drop all their bombs, and then send the army in. It’s really something.

I turn to Jack to translate, but he is tired from the day’s activities, and stares dully out the window. Strangely, I am relieved. I don’t need to translate everything.

***

The monks set off with the three-year old boy’s body around eight a.m., but we do not get wind of their absence until half an hour later. Eager to gain at least a glimpse at the ceremony, Jack and I hurry down the path, Carrie and Erik reluctantly in tow. We reach a point about a hundred yards below the site, where we can only see the tops of the tallest prayer flag poles. It is a gray and drizzly morning, and our clothes are dark with damp.

Out of respect for the dead, Carrie refuses to go on any further. Jack and I dare to walk ahead, Carrie hissing after us, No, don’t! We round a lazy corner of the hill on the path and face the burial ground, but from our vantage point it is completely empty. In the distance, we see two monks walking off, taking another path back to the monastery. They are unhurried, yet their robes flap excitedly. Above us, the falcons and vultures circle in perfect spirals. Some land and disappear from view, and others rise to take their place. There are so many of them that they seem to be whipping up the wind they glide on.

***

On my final night in China, I have dinner with my distant cousin Rong Rong. More worldly than most Beijingers, Rong Rong is a tour leader for a travel agency and has been to India and Thailand. She is the only connection left to my former days in Beijing, and I am happy to see her. I am surprised at her southeast Asian tan and her nose ring, but she makes no note of my new goatee, my thinning hair. Her casualness forces me to think a bit: Have we seen each other recently? No, it was three years ago.

We walk alongside Houhai Lake. It is located in the center of Beijing, and yet it is as if we are in the country: dark still waters, winding pathways, a few isolated cafes with hammock-like bamboo chairs stationed at the water’s edge. Every so often boats pass by, local and foreign tourists lounging inside as a woman plays her zheng on her lap. Plucked notes rain out and trickle in a wake behind the boat.

Rong Rong and I recall old days, like the time I tried paying for a meal at Pizza Hut with my credit card, and was rebuffed by the cashier. I threw a temper tantrum in which I claimed that the Chinese know nothing about business, and Rong Rong in turn criticized my pettiness. In the end, my credit card was processed after all, and Rong Rong thrust money at me, insisting she pay for her share of the meal. I refused it. She literally threw it in my face. I let the scraps of bills fall to the sidewalk, and we both walked on, sullen and identical. We can laugh about it now, and I reflect that there is real power that comes from stewing in righteousness.

I ate at Pizza Hut today, I told her. For old time’s sake. They still don’t have enough tomato sauce.

I’m surprised you came back, she counters. I thought you didn’t like China.

Oh yes? I say. I don’t mind anything, as I am drunk on plum wine.

But you are here again, so I guess you like it a little bit.

Sure, I laugh. A little bit.

A man and a woman are standing at the water’s edge. The man is folding magazine sheets, fashioning little square boats. The woman is carefully placing candles in the center of each boat. The man lights a candle with his cigarette and hands it to the woman. The woman lets some wax drip into the boat’s hull. The candle is successfully planted, and the process is repeated. They release each finished boat into the lake and blow at it gently, for they do not dare push at the water and possibly capsize the vessel. Already a string of two dozen boats are floating towards the barely visible shore on the other side of the lake.

Rong Rong asks if she can launch a vessel and the couple obliges. She sets it gravely on the water’s surface and watches as it joins the flotilla. The couple pause in their work and join us at the water’s edge. We’re all smiling, feeling free and easy and completely absorbed by the progress of these boats. It is a windless night, and the boats drift out to the middle of the lake, their candles burning bright, like a procession of lanterns. It is unlikely they will reach the other shore before the candles give out, but already they are congregating together in easy harmony. Each ship could hold a crew, a family, a collection of pilgrims seeking a safe haven. ■

Originally published in the Winter 2002 edition of Caveat Lector.